Beyond High vs. Low: Is Glycemic Index Key to Healthy Carbs?

With recommendations to limit consumption of sugar and refined grains, and focus on “quality carbohydrate”, how can you choose foods that support your goal of healthy eating?

Is glycemic index (GI) or glycemic load (GL) the key? What about amount and types of fiber, prebiotics, or whole grains?

Without going overboard based on “health halos”, how can you identify and include quality carbs in your day-to-day eating habits? Here, in Part One

on choosing healthy sources of carbohydrates, we’ll look beyond the headlines at glycemic index….

Is Glycemic Index the Answer?

Glycemic index (GI) is a way of defining the rise in blood sugar over a two-hour period after eating foods with equal amounts of carbohydrate. You’ve probably seen headlines linking high GI or high glycemic load (GL, which takes into account the portion of food) with greater risk of chronic disease or greater challenge with overweight. Those headlines might make GI figures seem like a simple, clear-cut guide to what’s in and what’s out for healthy eating. However, when researchers put individual studies into the big picture, combining multiple large studies, analysis is not consistent enough to rely on GI or GL to identify eating habits for lower risk of heart disease or cancer, or for more effective weight loss.

“Glycemic” Effects of Food Do Matter

Blood sugar surges after eating matter, whether or not you have diabetes. Soaring blood sugar calls for the body to pump out more insulin to handle the sugar, and over time, this increased demand can wear out the pancreas, and increase risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Moreover, high blood sugar travels to the liver, which converts it to fat. This fat is then stored in the liver, raising risk of NAFLD (non-alcoholic fatty liver disease), and circulates in the blood (as triglycerides), raising heart disease risk.

It’s unclear how much blood sugar itself affects cancer risk, but good evidence shows the high levels of insulin resulting from blood sugar surges can increase growth of cells that lead to cancer. High levels of insulin also result in higher levels of circulating estrogen available to promote estrogen-sensitive cancers.

When Glycemic Index Leads You Astray

- Portion matters. Glycemic index rates food based on blood sugar rise following portions that supply 50 grams of carbohydrate. That allows comparison of different sources of carbohydrate gram-for-gram. But it is misleading, since the results may not reflect your portions. People who don’t eat carrots because of their glycemic index are missing the fact that carrots’ “high” score refers to eating more than a pound of raw carrots. A normal portion could provide plenty of nutrients without harmful effects on blood sugar.

- Preparation matters. Lumping all forms of a food together overlooks evidence that effects on blood sugar vary substantially depending on preparation and what else is eaten at the same time. For example, baked potatoes’ carbohydrate isn’t absorbed as quickly as that from mashed potatoes. Carbohydrate in potatoes that have been cooked and cooled (as for potato salad) is more slowly absorbed from the digestive tract than that from potatoes cooked and eaten right away. Likewise, less-ripe bananas cause a slower rise in blood sugar than those that are more ripe; pasta cooked al dente doesn’t send blood sugar as high as pasta cooked to a softer state.

- Nutrient content matters. If you use GI or GL to define “healthy”, that makes a pizza loaded with sausage and pepperoni a healthier choice than a marinara or margherita pizza with tomato sauce, mozzarella and basil. Peanut M&Ms would be a healthier choice than raisins or cherries. By all other standards of nutrition, that does not make sense.

- Total calories matter. It’s easy to give low-GI or low-GL foods a “health halo ”, and assume that portions don’t matter. But they do. Getting plenty of vegetables as part of healthy eating choices provides filling bulk with few calories. That’s different than polishing off a jar of peanuts in one sitting, ignoring the calorie load because they are low in GI.

Putting GI and GL in the Big Picture

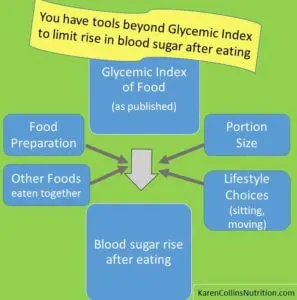

Despite tests that assign a GI or GL score to a food, multiple factors may contribute to inconsistency in how that food actually affects blood sugar in different people under different circumstances. A Tufts University study shows that even among relatively similar conditions, GI of a food varies by 25 % among different individuals (none of whom had diabetes, prediabetes or medications affecting blood sugar). In fact, blood sugar effects of a food in the same individual varied by 20% among six different tests over a 3-month period.

Glycemic index can be a tool that helps us understand how different carbohydrate-containing foods affect blood sugar – and health – differently. However, that doesn’t make it a criterion independent of other characteristics you already use to identify healthy food choices.

Avoiding Sugar & Insulin Surges

Without tying yourself to “eating by the numbers”, you can use the principles learned from research with glycemic index to create strategies to avoid unhealthy surges in blood sugar and insulin after eating. As an obvious starting point, limit sweet drinks and refined grains (such as white bread, bakery and candy). Choosing nutrient-rich whole plant foods pays off in multiple ways beyond blood sugar effects. Beyond that…

- Don’t overdo carbohydrate-rich foods at one time. A big bowl of pasta is best accompanied by a substantial salad or hearty bowl of soup, not a never-ending bread basket. If you have delicious fresh bread, then save the pasta feast for another night, or keep portions of both modest. (This may not apply to certain athletes or individuals with very high calorie needs, but this approach makes good sense for most adults.)

- Enjoy carbohydrate-containing foods as part of healthy meals, where fat, protein and viscous fiber (like that in beans, vegetables, fruits, and grains like oats and barley) help slow the rate of food emptying from the stomach.

- Mediterranean-style dishes add olive oil (or other oils) to prepare or flavor roasted or stir-fried vegetables, salads, and grains. Healthful fat from appropriate portions of nuts and avocado help, too.

- Acidic flavorings, such as lemon juice and vinegar, add zest as salad dressing or a splash on vegetables, seafood and poultry. They also slow gastric emptying of foods in a meal.

- Black beans, chickpeas, lentils and other pulses are traditional pairings with grains in traditional dishes throughout the world. They’re rich in nutrients and protective phytochemicals (natural plant compounds), in addition to their glycemic-helpful viscous fiber.

- Research is in progress on how the natural compounds from vegetables, fruits, whole grains and beans may provide help through long-term protection against chronic inflammation and insulin resistance through effects on cell signaling pathways.

- Don’t overlook physical activity’s ability to reduce insulin resistance and help control blood sugar! A ten-minute walk right after eating may be especially effective to limit rise in blood sugar following a meal, according to emerging research. Swapping even an hour of sitting time for any form of movement, breaking up periods of extended sitting, and strength-training exercise all help improve insulin sensitivity.

Bottom Line on Glycemic Index for Healthy Eating:

Theoretically, eating foods with a high glycemic index (GI), which make blood sugars rise higher and faster right after eating, could cause metabolic and hormonal effects that increase risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, some cancers, and weight gain. However, though books and websites list foods’ GI values, effects on your blood sugar change substantially depending on how a food is prepared, what’s eaten with it, and how big a portion you take, as well as the overall healthfulness of your eating and exercise habits. GI and GL may be a good starting point if you’re working with a registered dietitian nutritionist (RD or RDN) to determine how different foods affect your blood sugars. We all need to remember, however, that although healthy diets tend to be low in glycemic load (GL), not all low-GI or low-GL eating habits are necessarily healthy.

Come back for Part 2 of this look at how to improve the quality of the carbohydrate you eat as part of overall eating habits that promote health and vitality.

Sign up: If you aren’t already receiving my research reviews by email, sign up so you won’t miss Part 2 and other exciting posts! Just click here.

For practical ideas on ways to limit rise in blood sugar after eating, check this from Oldways Preservation Trust: A Dozen Tips for Better Blood Sugar Control: Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load.

American Diabetes Association. Lifestyle Management. Sec. 4 in: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2017. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40(Suppl. 1):S33-S43.

Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31(12):2281-2283.

Augustin LS, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015 Sep;25(9):795-815.

Dempsey PC, Owen N, Yates TE, Kingwell BA, Dunstan DW. Sitting Less and Moving More: Improved Glycaemic Control for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention and Management. Curr Diab Rep. 2016; 16: 114.

Keadle SK, Conroy DE, Buman MP, Dunstan DW, Matthews CE. Targeting Reductions in Sitting Time to Increase Physical Activity and Improve Health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001257. [Epub ahead of print]

Kristo AS, Matthan NR, Lichtenstein AH. Effect of diets differing in glycemic index and glycemic load on cardiovascular risk factors: review of randomized controlled-feeding trials. Nutrients. 2013; 5(4):1071-80.

Mann S, Beedie C, Balducci S, et al. Changes in insulin sensitivity in response to different modalities of exercise: a review of the evidence. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2014; 30(4):257-268.

Matthan NR, Ausman LM, Meng H, Tighiouart H, Lichtenstein AH. Estimating the reliability of glycemic index values and potential sources of methodological and biological variability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016; 104:1004-1013.

Melanson KJ, Summers A, Nguyen V et al. Body composition, dietary composition, and components of metabolic syndrome in overweight and obese adults after a 12-week trial on dietary treatments focused on portion control, energy density, or glycemic index. Nutr J. 2012; 11:57.

Mirrahimi A, Chiavaroli L, Srichaikul K et al. The role of glycemic index and glycemic load in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors: a review of the recent literature. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014; 16(1):381.

Mullie P, Koechlin A, Boniol M, Autier P and Boyle P. Relation between Breast Cancer and High Glycemic Index or Glycemic Load: A Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016; 56(1):152-9.

Reynolds AN, Mann JI, Williams S et al. Advice to walk after meals is more effective for lowering postprandial glycaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus than advice that does not specify timing: a randomised crossover study. Diabetologia. 2016; 59(12):2572-2578.

Smith AD, Crippa A, Woodcock J, Brage S. Physical activity and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetologia. 2016; 59(12):2527-2545.

Turati F, Galeone C, Gandini S, et al. High glycemic index and glycemic load are associated with moderately increased cancer risk. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015; 59(7):1384-1394.

2 Comments

Leave a Comment

Published : April 24, 2017

Tagged: cancer prevention, carbohydrates, carbs, glycemic index, glycemic load, healthy diet, healthy eating, healthy lifestyle, heart health, insulin resistance, reducing cancer risk, sedentary lifestyle, vegetables, weight control, weight loss, whole grains

Meet the author/educator

I Take Nutrition Science From Daunting to Doable.™

As a registered dietitian nutritionist, one of the most frequent complaints I hear from people — including health professionals — is that they are overwhelmed by the volume of sometimes-conflicting nutrition information.

I believe that when you turn nutrition from daunting to doable, you can transform people's lives.

Accurately translating nutrition science takes training, time and practice. Dietitians have the essential training and knowledge, but there’s only so much time in a day. I delight in helping them conquer “nutrition overwhelm” so they can feel capable and confident as they help others thrive.

I'm a speaker, writer, and nutrition consultant ... and I welcome you to share or comment on posts as part of this community!

[…] Smart Bytes® series on carbohydrate quality looked at evidence and take-home strategies on what glycemic index and eating more pulses mean for health. In this third post in the series, I’ll address some top […]

[…] Part 1 of this series on carbohydrate quality, we talked about the problems of using glycemic index to define a healthy carb. In Part 2, let’s consider what research shows about legumes for […]